Forgotten Female Tycoon of Medieval London: The Grocer's Widow

Discover the forgotten female tycoon medieval London history forgot - Annabell Furner, grocer's widow who built an international trading empire.

MEDIEVALWOMENS HISTORY

6/16/202510 min read

How Annabell Furner Commanded London's Spice Trade While Kingdoms Crumbled

In 1437, while King James I of Scotland was brutally murdered and Europe descended into political chaos, one woman in London was quietly building an international trading empire. Hidden in banking records for over 600 years, the story of Annabell Furner challenges everything we thought we knew about medieval women's economic power.

Meet medieval London's forgotten female tycoon - a grocer's widow who commanded spice routes, negotiated with Italian bankers and wielded financial influence that would make modern CEOs envious. Her story, preserved in the digitised records of the Borromei Bank Research Project,¹ reveals the hidden women's history of medieval London.

How Medieval Women Became Business Owners in London

Annabell's story exemplifies a broader pattern of forgotten female merchants in medieval London's commercial elite that has been largely written out of popular history. Contrary to common assumptions about medieval women's exclusion from formal trade organisations, there is evidence of women becoming members of London's powerful livery companies through widowhood.

As a grocer's widow, Annabell operated with the independent legal status that widowhood automatically conferred, allowing her to conduct business without male guardianship. This enabled her to inherit her deceased husband's commercial enterprise and continue operating within the networks of the prestigious Grocers' Company. While there is no surviving record of her formal membership, the scale of her wholesale business makes it highly likely that she inherited her husband's company privileges, as was common practice for widows in this period.

It is important to distinguish this from the rarer femme sole merchant status, which was a special legal arrangement that allowed some married women in urban contexts like London to act "as if single" for business purposes. This status, which often involved registration with town authorities, enabled married women to conduct business independently and to be held liable for their own business debts separate from their husbands. However, most women who enjoyed business autonomy did so as widows like Annabell, rather than through the exceptional femme sole merchant arrangement which remained uncommon and was mainly found among artisans and traders in specific urban environments.

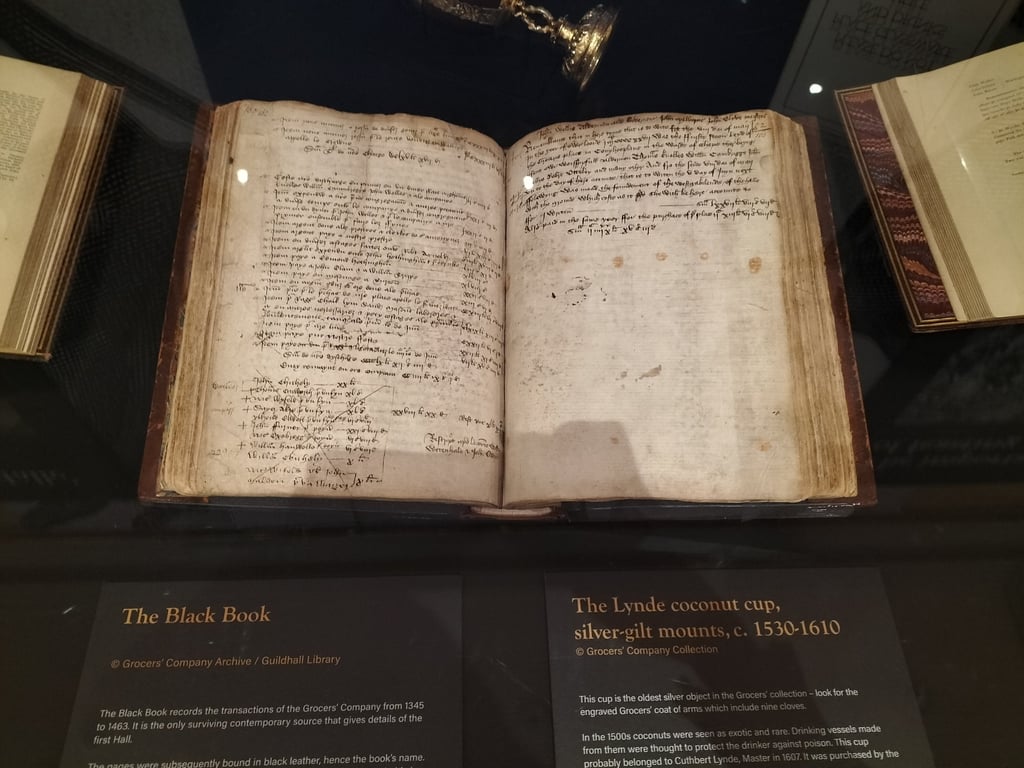

The Secret World of Medieval London's Merchant Elite

Annabell's position as a grocer's widow placed her within one of London's most exclusive commercial organisations. The Grocers' Company, established in 1345 and ranked second among the Great Twelve livery companies, regulated and represented merchants engaged in international wholesale trade rather than local retail. Medieval "grocers" were not shopkeepers but wholesale traders dealing in bulk commodities - exotic spices, dried fruits and luxury goods imported from across Europe and the Mediterranean. Membership in the company indicated significant commercial status and access to trading networks that stretched from London to Constantinople.

The company's acceptance of widows like Annabell as continuing members reflected both legal precedent and economic necessity. Established trade relationships with international suppliers and English distributors represented valuable commercial assets that companies were reluctant to lose through strict gender exclusions.

The Bank Records That Reveal a Forgotten Female Tycoon

The Borromei Bank records document Annabell's participation in high-value commodity trading that confirms her active participation in London's commercial elite.¹ Her transactions reveal sophisticated commercial practices characteristic of international wholesale trade.

A July 1437 entry records a transaction that would shock modern assumptions about medieval women: 'For one sack of saffron sold to her, gross weight lb. 61, packaging lb. 4 and [allowance for] packaging at 4% lb. 2 on. 4 1/2, net weight lb. 54 on. 11 1/2 at s. 14 per lb., £38 6s 0d. Time to pay: 1 November next"¹

To put this in perspective: £38 could support a skilled craftsman's household for 6-8 years or maintain a modest commercial household with several servants for a year

The detailed weight calculations, including packaging allowances, indicate standardised measurement practices essential for international trade. The extended payment terms reflect the credit-based nature of wholesale commodity trading that required trust relationships spanning months across different countries and currencies.

Multiple entries show transactions with extended payment schedules, such as "Time to pay: half in 4 months, half after another 4 months,"¹ proving her participation in the sophisticated credit networks that facilitated medieval international trade. These arrangements required financial knowledge that historians assumed women didn't possess.

Why Medieval Women's Business Success Was Hidden from History

Annabell's case fits within a larger pattern of forgotten female merchants in medieval commercial organisations. The evidence from her documented trading activities suggests that women's involvement in London's wholesale commodity trade was far more extensive than traditionally recognised, particularly during the earlier medieval period.

Women members did not possess substantial political rights within the City of London's governance structure during the medieval period. While widows could regularly be admitted to the freedom of the City through inheritance to continue their late husbands' businesses, this economic privilege was exceptional in that it did not translate into voting rights for sheriffs or other city officials. The legal and customary framework of medieval times generally excluded women from direct participation in civic elections and high office.

Women's participation in guilds and liveries was limited in multiple ways. Evidence suggests that whilst widows could become members and could take over businesses and the training of apprentices, they were often excluded from broader participation including company business decisions - the very meetings where their contributions would have been recorded for posterity. Their formal status was typically derived through their husbands or fathers and their ability to act independently was heavily constrained by both custom and law.

Furthermore, women's position in guilds and liveries deteriorated over time as restrictions were increasingly placed on women's work and these organisations became increasingly male-only. This pattern suggests that Annabell operated during a period when women's commercial opportunities, while already constrained by patriarchal structures, were more extensive than they would become in later centuries.

The International Trading Empire of a Medieval Businesswoman

The scale and sophistication of Annabell's documented transactions indicate that she successfully maintained and possibly expanded her inherited wholesale business. Her trades focus on high-value commodities, particularly saffron and cotton, that required access to Mediterranean supply networks and sufficient capital to invest in luxury goods with lengthy transport chains.

The records document her cotton trading with entries noting 'For two sacks of cotton sold to her: gross weight lb. 1044, packaging for the sacks lb. 38 and for 4% lb. 40, net weight lb. 966 at d. 4 per lb., £16 2s 0d.'¹ This transaction's scale - nearly 1000 pounds of cotton - demonstrates wholesale-level trading operations that place her among London's significant commodity traders.

To understand the significance: saffron required approximately 150 flower stigmas to produce just one gram, making it more valuable than silver. Annabell wasn't just trading spices - she was dealing in concentrated wealth that connected London dinner tables to harvest fields across the known world.

The extended payment terms and complex credit arrangements in her transactions reflect the seasonal nature of medieval trade and the time required to distribute wholesale commodities across England's challenging transport networks. Such arrangements were essential for wholesale traders who needed to coordinate supply with distant markets and seasonal demand cycles.

Medieval London's Surprising Financial Sophistication

The Borromei Bank itself, with operations in both Bruges and London, exemplified the international financial networks that made Annabell's trade possible. The bank's meticulous record-keeping, noting currency conversions and complex payment terms, provides evidence of the sophisticated financial infrastructure supporting medieval commerce that rivals modern banking in its complexity.

Annabell's ability to access these international financial services indicates her integration into the commercial networks that connected London to continental European markets. Her transactions show dealing in multiple currencies and complex credit arrangements that required knowledge of international exchange rates and commercial law - skills that challenge fundamental assumptions about medieval women's commercial capabilities.

What This Reveals About Medieval Women's Economic Power

Annabell Furner's documented commercial activities contribute significantly to our understanding of women's roles in medieval economic life. Her case demonstrates that some women possessed substantial commercial autonomy and participated actively in international trade networks, operating at the highest levels of London's wholesale commodity trade.

The evidence also illuminates the practical operation of medieval trade networks, showing how London merchants connected English markets to international supply chains through sophisticated financial instruments and credit relationships. Annabell's success suggests that commercial competence, rather than gender, determined business outcomes within the legal frameworks available to widows operating under femme sole status.

Her documented transactions provide concrete evidence that medieval London's commercial elite included women who wielded substantial economic influence. This challenges assumptions about the exclusively male nature of medieval international trade and demonstrates the significant role that capable widows could play in continuing major wholesale trading operations.

Why These Remarkable Women Disappeared from History

The trajectory of women's participation in liveries and guilds helps explain why figures like Annabell have been largely forgotten by history. As these organisations became more politically powerful and economically exclusive, they gradually restricted women's membership and participation, though this process was uneven and varied significantly between different companies and regions. Some liveries and guilds started restricting women earlier than others, whilst some retained traces of female participation well into the early modern period.

This historical trajectory means that the medieval period represents a conditional window when some women could achieve commercial success through membership of liveries and guilds - typically as widows, daughters or occasionally as femmes soles, though they were often excluded from holding office or achieving full membership. Annabell's level of international commercial activity would have been highly unusual for any woman of her time, as most women's commercial activity remained local or regional, making her saffron and cotton trading exceptionally rare rather than representative.

The gradual exclusion of women from records of liveries and guilds means that their earlier participation was slowly erased from institutional memory. This erasure resulted not only from changing membership rules but also from record-keeping practices that prioritised men's activities even when women were active participants, compounded by broader changes in legal frameworks around women's property and business rights. This left only fragments in sources like banking records to hint at women's once-significant, though always somewhat limited and conditional, role in medieval commercial life.

Evidence Hidden in Plain Sight

The Borromei Bank records provide rare quantitative data on medieval women's commercial activities that complement the limited evidence from other sources.¹ Unlike narrative sources that often focus on exceptional cases, these banking records document routine commercial transactions, offering insight into the regular patterns of women's participation in business and trade in late medieval London.

The systematic nature of the bank's record-keeping allows for analysis of transaction patterns, commodity flows and financial instruments that would be impossible with less complete documentation.¹ These records demonstrate that the commercial activities of women like Annabell were substantial enough to warrant detailed documentation in international banking records - evidence of their significant role in medieval London's economy that historians missed for centuries.

Annabell Furner's story, preserved in Italian banking ledgers for over 600 years, challenges us to reconsider how many other women's contributions to medieval commerce remain buried in archives across Europe..

FAQS

What is the Borromei Bank Research Project? The Borromei Bank Research Project is a collaboration between Queen Mary University of London and partner institutions that digitises and analyses medieval banking records from the 15th century. The project provides access to detailed financial records that document international trade in medieval London.

What exactly was a "grocer" in medieval London? Medieval grocers were not shopkeepers but wholesale merchants who traded in bulk commodities like spices, dried fruits and luxury goods. They were among London's commercial elite, importing goods from across Europe and the Mediterranean and distributing them throughout England.

What is femme sole status? Femme sole was a legal doctrine that allowed widows to conduct business independently, separate from male guardianship. This status enabled women like Annabell to inherit and operate commercial enterprises in their own right.

How much was £38 worth in 1437? £38 represented substantial wealth in medieval terms. To put this in perspective, a skilled craftsman in the 1430s-1440s earned approximately £5-6 per year (5-6d per day across ~250 working days), making Annabell's single saffron transaction worth approximately 6-8 years of a skilled craftsman's wages.

Why are the names written differently in the records (like "Forner, Forneria")? The Borromei Bank was run by Italian clerks who adapted unfamiliar English names to Italian spellings or phonetic equivalents. "Furner" became "Forner" or "Forneria" as the Italians tried to render the English name in a way that made sense to them.

Could women really be members of medieval guilds? Yes, though typically through specific circumstances like widowhood. The guilds needed to maintain commercial continuity, so excluding capable widows would have damaged established business relationships. However, women often faced restrictions on their participation in guild governance.

Why don't we know more about women like Annabell? Women's commercial activities were often overshadowed by their male relatives in historical records, and many guild records focus on formal meetings and governance where women were excluded. Banking records like these are rare sources that document women's actual business activities.

How did international banking work in medieval times? Medieval banks like the Borromei operated across multiple cities, providing credit arrangements, currency exchange and payment services for international merchants. They maintained detailed records and enabled complex trade relationships across different countries and currencies.

Why was saffron so valuable? Saffron required the stigmas of approximately 150 flowers to produce just one gram, making it extremely labour-intensive to harvest. It was more valuable than its weight in silver and was essential for luxury cooking, medicine and dyeing.

How common were female merchants in medieval London? While the exact numbers are unknown, evidence suggests female participation in commerce was more common than traditionally thought, particularly among widows who inherited businesses. However, their opportunities decreased over time as guilds became more restrictive.

Discover More Hidden Stories: The Mysterious Black Tudors City of London Walk

Annabell Furner's story is just one thread in the rich tapestry of forgotten figures who shaped the City of London. If you're fascinated by these hidden histories, join us on the Mysterious Black Tudors City of London Walk, where we explore the untold stories of diversity in medieval and Tudor London.

On this guided walking tour, you'll discover:

The remarkable Black Tudor who became a member of a London livery company, challenging assumptions about Tudor diversity

Hidden guild halls and ancient streets where Tudor merchants built upon medieval trading traditions

Stories of Black Tudors who thrived in the City and beyond

Why "race" meant something very different in Tudor England - and what that changes about how we read history

Perfect for: History enthusiasts, anyone interested in diverse narratives, and those who want to see London through fresh eyes.

Book Your Mysterious Black Tudors Walk Today and discover the City's hidden diversity that most visitors never hear about.

Because the best stories are the ones they forgot to tell.

References

¹ J.L. Bolton and F. Guidi-Bruscoli, The Borromei Bank Research Project, online database, https://www.qmul.ac.uk/borromei-bank-research

These transactions were discovered through original research in the Borromei Bank Research Project database (www.qmul.ac.uk/borromei-bank-research), a digitised collection of Italian banking records from 1436-1439. The database preserves approximately 23,000-25,000 transactions and is searchable by keyword, name, and commodity. Annabell appears in the London ledger as 'Furner, Annabell, widow of a grocer [Forner, Forneria]' with multiple transactions recorded between July 1437 and September 1438.

Explore

Discover the hidden stories of Britain's Tudors.

Connect

Subscribe to Newsletter

contact@hiddentudorstours.co.uk

+44 (0)203 603 7729

© 2025. All rights reserved.