John Blanke: The Black Tudor Trumpeter's 1512 Marriage and Pay Rise

John Blanke, Henry VIII's Black trumpeter, married in 1512 and successfully petitioned for a pay rise. Discover his remarkable Tudor story and what happened next.

BLACK HISTORYTUDOR

1/2/20268 min read

14 January 1512

On 14 January 1512, Henry VIII did something remarkable. He ordered his Great Wardrobe to prepare a wedding gift for one of his court trumpeters—a man who had played at his father's funeral, performed at his coronation and whose image appears twice in the magnificent Westminster Tournament Roll. The trumpeter's name was John Blanke and he was Black.

The gift was generous: four yards of furred violet cloth, a lined black doublet, scarlet hose, a hat and a bonnet, costing the considerable sum of £9 (approximately £27,000 in today's money). But the real story is not just about royal generosity. It is about what this marriage tells us about Black life in Tudor England, about the woman whose name we will never know, and about a world far more diverse than we have been taught to imagine.

John Blanke's Wife: A Mystery Lost to History

Her name is lost to history. The records that might have told us—parish registers, marriage licences, witness statements—either never existed or have not survived the five centuries since that January wedding. What we do know is this: John Blanke married in early January 1512, probably at St Nicholas Church in Deptford, close to the royal residence at Greenwich Palace where he worked.

Historians, including Dr. Miranda Kaufmann, author of Black Tudors: The Untold Story, suggest Blanke's bride was likely English. This was not unusual. Tudor England, before it became heavily involved in the transatlantic slave trade, was a place where interracial marriages occurred and were accepted. Parish records from across the country tell us of these unions: in 1599, John Cathman married Constantia, described as "a Black woman and servant" at St Olave Hart Street. A man named James Curres, noted as "a moore Christian," married Margaret Person, a maid.

Marriage Requirements for Black Tudors in 1512

To marry in Tudor England required one absolute: both parties had to be Christian. England was still a Catholic country in 1512, five years before Martin Luther nailed his theses to a church door in Germany, fifteen years before Henry VIII would begin his break with Rome. For John Blanke to marry in a church ceremony, he would have needed to be baptised. Whether he converted specifically for this marriage or had long been a Christian, we cannot know. We also do not know which church they married in—parish registers were not mandatory until 1538, and even then, many early records have not survived.

We know that Black Tudors were baptised, married, and buried by the Church throughout the sixteenth century. More than sixty Africans were baptised in England between 1500 and 1640. Take Mary Fillis, born in Morocco in 1577, who came to London as a child and was baptised at St Botolph's in 1597. These were not exceptions—they were part of Tudor life.

John Blanke's Wages and His Petition for a Pay Rise

John Blanke did something bold. He petitioned Henry VIII for a promotion and pay rise. The petition itself is undated, but historians believe it was submitted sometime around 1511 or early 1512, likely connected to his marriage plans. Blanke was already one of eight royal trumpeters, but he was paid less than his colleagues. In his petition, preserved in The National Archives, Blanke explained that his current wages—8 pence per day (approximately £105 per day in today's money)—were "not sufficient to mayntaigne and kepe hym to doo your grace lyke service as other your trompeters doo." His fellow trumpeters earned 12 or 16 pence daily. Blanke asked to be promoted into the position left vacant by the death of another trumpeter, Dominic Justinian, which would double his wages to 16 pence per day (approximately £210 per day today).

Why was Blanke paid less than his colleagues? The records do not explain, but the petition itself provides clues. He was not simply asking for more money—he was requesting promotion to "the same Rowme [position] of Trompete which Domynyc desessed late had." This suggests a hierarchical structure within the trumpeters, where junior positions earned 8 pence and senior positions earned 16 pence per day. What matters most is Henry VIII's response: he granted the petition immediately and even backdated the pay rise to 1 December (though we do not know which year). This was not the response of a king who believed a Black trumpeter deserved less than his white colleagues. It was the response of a king who recognised that Blanke had earned his promotion.

The timing is telling. Marriage in Tudor England meant setting up a household, and that required money. Blanke's petition suggests a man thinking about his future, about providing for a wife, perhaps about the possibility of children. It shows confidence, too—the confidence of a man who knew his value to the king and was not afraid to argue for it.

What Happened to John Blanke After 1512?

Here's what frustrates historians: after that generous wedding gift in January 1512, John Blanke disappears from the records. He does not appear in the next full list of royal trumpeters, compiled on 31 January 1514. Where did he go?

Some historians suggest he may have joined the disastrous English military expedition to France in the summer of 1512, where many men died. As a Spanish speaker (he likely came to England with Catherine of Aragon's entourage in 1501), his skills might have been valued. Others speculate he found better-paying work at another court, or that marriage gave him the opportunity to change professions—not uncommon for court servants, who sometimes married widows and took up their late husbands' trades.

We do not know if he and his wife had children. We do not know if she survived him or he her. We do not know if they were happy.

Black Women in Tudor England: What We Know

While we cannot know John Blanke's wife specifically, we can piece together what life might have been like for Black women in Tudor England from the fragments that survive.

They came in three main ways: directly from Africa with English merchants, from southern European countries with larger Black populations (like the servants of Portuguese doctor Hector Nunes), or as a result of privateering, when English ships captured Spanish or Portuguese vessels. Once in England, most became domestic servants. In larger households, they had specific roles—Grace Robinson worked as a laundress at Knole in Kent. In smaller homes, they took on a wider range of tasks but still had opportunities to acquire skills.

Mary Fillis's story is particularly instructive. Described in parish records as "Mary Fillis of Morisco," historians disagree about her origins. Dr. Miranda Kaufmann argues she came from Morocco, while Dr. Onyeka Nubia suggests she may have come from Andalucia's Morisco community—Muslims who had been forcibly baptised in Spain but were suspected of secretly practising Islam (crypto-Muslims). If she was a Morisco, her 1597 baptism in England would have been essential to prove her genuine Christian faith in her new country. Arriving in England as a child in the 1580s, she first worked in the comfortable household of merchant John Barker. Then she made a brave choice: she left to work for the more modest Mistress Porter, where she could learn new skills that would help her become more independent. This was not the decision of someone trapped or enslaved—it was the choice of a free woman thinking about her future.

The evidence shows that Black women in Tudor England, like Black men, enjoyed a status radically different from what would come later. As Dr. Kaufmann's research demonstrates, "there was little prejudice against interracial marriage in Tudor England." Tudors were far more likely to judge people by their religion and social class than by the colour of their skin. This would change dramatically once England became involved in the transatlantic slave trade, but in 1512, a different world was possible.

Why John Blanke's Marriage Matters for Tudor History

John Blanke's marriage matters precisely because we know so little about it. The very ordinariness of it—a working man marrying, receiving a gift from his employer, trying to negotiate better pay to support his household—tells us that Black Tudors participated fully in the social and economic life of their communities.

The generous wedding gift from Henry VIII suggests that Blanke was valued, that his service was appreciated. The fact that he felt confident enough to ask for a pay rise shows he understood his worth. The fact that he married at all, in a church, with royal approval, demonstrates that he was free—not enslaved, not marginal, but an integrated member of Tudor society.

His wife, whoever she was, was part of this story. She chose to marry him or they chose each other (love matches were not uncommon, even if families often had say in arrangements). She stood with him in a church somewhere in or near London, and made her vows. She became his partner in building a household, in navigating the complexities of Tudor life.

Where to See Evidence of John Blanke Today

Today, you can walk the streets of Deptford where a church dedicated to St Nicholas has stood since medieval times. While the church building from 1512 was demolished and rebuilt in 1697, the site remains the same, and part of the medieval tower (dating from around 1500) still stands. The current building now occupies the Old Royal Naval College site, where Henry VIII's Greenwich Palace once stood—where Blanke played his trumpet and negotiated his pay rise.

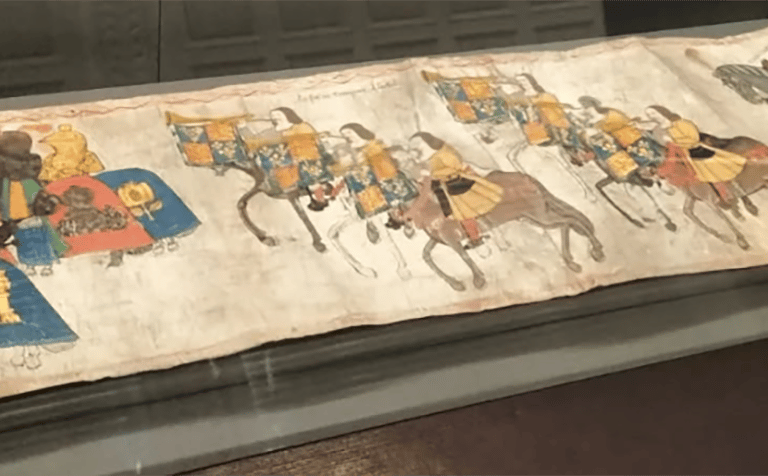

Inside the College of Arms is the Westminster Tournament Roll, where John Blanke appears twice, mounted on horseback, his turban distinctive among the bare-headed English trumpeters, his trumpet decorated with the royal arms. In those images, we see not just Blanke but the world that contained him—a world where a Black trumpeter could serve two kings, marry whom he chose and argue for fair pay.

The woman he married is invisible in these images, as most Tudor women are unless they were queens or noblewomen. But she was there. She was real. And for a brief moment in January 1512, she and John Blanke were at the centre of a story that still matters five hundred years later.

Frequently Asked Questions About John Blanke

Who was John Blanke? John Blanke was a Black royal trumpeter who served at the courts of Henry VII and Henry VIII between 1507 and 1512. He is one of the earliest documented Black people in Tudor England with both written records and identifiable images.

Where can I see images of John Blanke? John Blanke appears twice in the Westminster Tournament Roll of 1511, held at the College of Arms in London. He is depicted mounted on horseback wearing a distinctive turban, playing his trumpet decorated with royal arms.

When did John Blanke marry? John Blanke married in January 1512. On 14 January 1512, Henry VIII ordered a wedding gift for him consisting of violet cloth, a black doublet, scarlet hose, a hat, and a bonnet, costing £9 (approximately £27,000 today).

How much did John Blanke earn? Initially, John Blanke earned 8 pence per day (approximately £105 per day in modern terms). After his marriage, he successfully petitioned Henry VIII for a pay rise to 16 pence per day (approximately £210 per day today), which the king granted and backdated.

What happened to John Blanke? After January 1512, John Blanke disappears from royal records. He does not appear in the 1514 list of royal trumpeters. Historians speculate he may have joined the English military expedition to France in 1512, found employment at another court or changed professions after marriage.

Who was John Blanke's wife? John Blanke's wife's name is unknown. No marriage records survive. Historians believe she was likely English, as interracial marriages were accepted in Tudor England and occurred regularly before England's involvement in the transatlantic slave trade.

Discover the world of John Blanke and other Black Tudors on Hidden Tudors Tours — London's premier Black history walking tours. Our historically accurate walks explore Tudor Westminster, Southwark's historic riverside, and the City of London, revealing how Black individuals lived, worked, and thrived in 16th-century England before modern racial constructs emerged. Join our expert guides to uncover the authentic, overlooked stories of African people in Tudor society—from royal trumpeters to skilled tradespeople. Perfect for history enthusiasts seeking London's diverse historical narrative beyond the conventional tourist trail.

Sources:

The National Archives (TNA): E101/417/6, no.50 (wedding gift warrant); E101/417/2 no.105 (pay petition)

British Library, Egerton MS 3025 (Great Wardrobe accounts 1511-12)

Dr. Miranda Kaufmann, Black Tudors: The Untold Story (2017)

Dr. Miranda Kaufmann, "Blanke, John (fl. 1507–1512), royal trumpeter," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Dr. Onyeka Nubia, Blackamoores: Africans in Tudor England, Their Presence, Status and Origins (2013)

Dr. Onyeka Nubia, England's Other Countrymen: Black Tudor Society (2019)

Historic Royal Palaces, John Blanke resource

Parish records (various, cited in Kaufmann's research)

Explore

Discover the hidden stories of Britain's Tudors.

Connect

Subscribe to Newsletter

contact@hiddentudorstours.co.uk

+44 (0)203 603 7729

© 2025. All rights reserved.